(Please read Matthew 18:21-35)

This parable concludes a chapter in Matthew in which the Lord details the extraordinary relations among members of His Church. In the kingdom of heaven, nothing is valued more than the simplicity of a child, so it is wicked to offend such souls; also, as a shepherd covers hill and dale to restore a wandering sheep, the church should undertake to restore to its fellowship the lost brother or sister.

That last part prompted Peter to ask, “How often shall my brother sin against me and I forgive him?” and to venture his own progressive-sounding suggestion: “seven times?” Jesus responded with the famous “up to seventy times seven.” (verses 21-22). That led into a parable likening the kingdom of heaven to the events described in the reading above.

This parable impresses the reader with several heavenly truths. One is the extraordinary gravity of our sins. Jesus likens the Father in heaven (verse 35) to “a certain king who wanted to settle accounts with his servants.” One unwilling minion was brought in who owed him “ten thousand talents.” There are too many variables with the word “talent” to calculate any hard number in modern terms, but that’s just fine, because the debt described is simply incalculable. We are talking about sin here, and there is no way humans can quantify what it means to disobey God. Tasting the forbidden fruit brought Adam and Eve to ruin, and their descendants with them. A cross word with a brother is equal to murder; a lustful thought no less wicked than an extra-marital affair (Matthew 5:22, 28). There is none among us who is not in the same extraordinary fix as this indebted servant.

When confronted by the reality of his debt, the servant dissolves into an unrealistic plea: “Have patience with me and I will pay you all.” What the servant was doing was the natural, flesh-based response to a spiritual crisis: work righteousness. “Wait, God—I can fix this.”

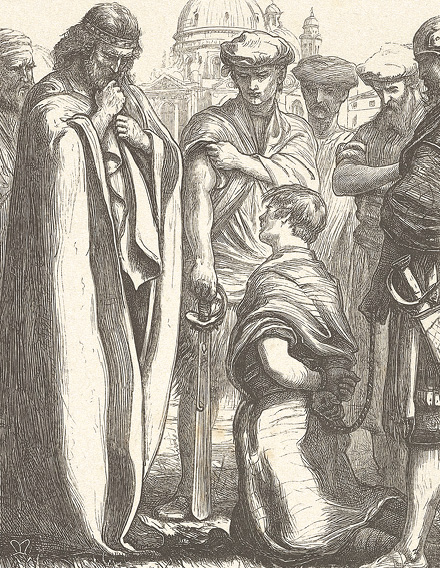

It was solely the master’s compassion that led to the next extraordinary move: he forgave him the debt, cleared him of all past obligations. This, of course, was the master’s prerogative, but let no one diminish the magnitude of such a move. It undoubtedly cost the master a lot to bear such a loss. The corollary here is what it cost the Father in heaven to forgive even one man’s debt: the redeeming death of His Son. The master’s move here is an example of God’s extraordinary grace in covering the debt that every one of us owes.

But the parable also exposes the extraordinary blindness humans are capable of in the face of such generosity and love. The servant comes across a fellow who owes him money. A far smaller debt, but not insignificant—perhaps a few months’ wages. These debts certainly occur and are part of living in this sinful world: damage to one’s property; broken trust; violent crime. But just as the servant’s actions are unbalanced and harsh, so also our sense of justice is often distorted and vindictive and out of proportion, both as to the offense we’ve borne and—even more—to the grace we have been shown. The master was not pleased.

We have all been forgiven the unforgivable; we all have our vast debts removed and are welcomed into good standing with our Lord God. Believing that, we have spiritual life and spiritual liberty to joyfully serve in the Lord’s vineyard. But we also still bear with us a corrupt nature, so ready to nurture a grudge. This parable confronts us with the extraordinary grace that we have received, and the extraordinary consequences of losing track of that grace in our own dealings with others.

is a former pastor who now teaches English at the University of Wisconsin-Stout. He makes his home in Eau Claire, Wisconsin.