“Then the Spirit said to Philip, ‘Go near and overtake this chariot.’ So Philip ran to him, and heard him reading the prophet Isaiah, and said, ‘Do you understand what you are reading?’ And [the Ethiopian] said, ‘How can I, unless someone guides me?'” (Acts 8:29-31)

Being directed by the Holy Spirit to approach the Ethiopian’s chariot and invited by the Ethiopian into the chariot, Philip became the man’s guide. We’re told, “Then Philip opened his mouth, and beginning at this Scripture, preached Jesus to him.” (Acts 8:35)

Martin Luther has been referred to as the Father of the Reformation and the Great Reformer. In his book The Church of the Reformation, Conrad Bergendoff uses the word guide to describe Luther’s work as a reformer. “He is not the creator of a new church but the guide to an understanding of the nature of the true church” (page 31). But Luther was also a guide on a personal level.

When the Ethiopian told Philip that he didn’t understand the Isaiah passage, Philip stepped into the chariot and “preached Jesus to him.” The preaching was understandable and effective. The Holy Spirit created faith in the man. Martin Luther, also, had an audience that he desired should know Scripture, so he “stepped into the chariot”—Germany—and preached Jesus. One thing Luther did to guide the people to a clear understanding of God’s Word was to present the Word in the vernacular—the language of the people.

Jesus tells us in the meaning of a parable the great importance of understanding Scripture: “When anyone hears the Word of the kingdom, and does not understand it, then the wicked one comes and snatches away what was sown in his heart.” (Matthew 13:19)

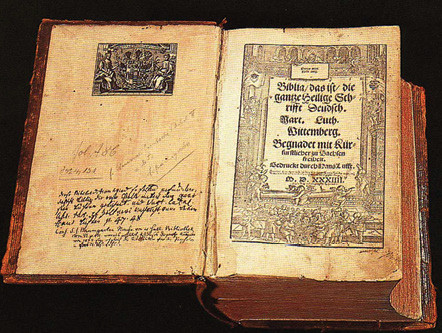

In Luther’s day (and well beyond), the Roman Catholic Church conducted mass in Latin, and most Bibles were in Latin. Latin was still in use, but mainly as the language of scholars—theologians and scientists—not the common man. Luther, understanding the needs of the people, spent much of his time at the Wartburg Castle translating the New Testament into German. He followed with the Old Testament. About the Bible, Luther once said, “Would that this one book were in every language, in every hand, before the eyes, and in the ears and hearts of all men!”

Luther did not write the only, or even the first, vernacular Bible. Other vernacular Bibles had been produced and were being produced around this time in Germany and other European countries.

Luther’s use of the vernacular expanded. He began to preach sermons in German. He promoted congregational singing, insisting that the hymns be in German. To this end, Luther wrote hymns for the congregation and encouraged hymn singing in the homes and in parochial schools. “His forms for baptism and marriage established an evangelical ministry in the vernacular that bound the family to the church.” (Bergendoff page 60)

Luther did not completely dispense with the use of Latin in services, using it for years in the Wittenburg church (Bergendoff page 53). Luther said, “For in no wise would I want to discontinue the service in the Latin language because the young are my chief concern. And if I could bring it to pass, and Greek and Hebrew were as familiar to us as is the Latin . . . we would hold mass, sing, and read on successive Sundays in all four languages, German, Latin, Greek, and Hebrew. I do not at all agree with those who cling to one language and despise all others.”

Vernacular language certainly helps us understand the Bible and worship, but Luther adds this: “Entreat the Lord to grant you, of His great mercy, the true understanding of His Word. . . trust solely in God, and in the influence of His Spirit.”

is a retired teacher. He lives in Kassota, Minnesota.