HEROES OF THE FAITH (SIXTH IN A SERIES)

As we approach the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, we take a brief look at the lives of some of the most influential and important Lutheran theologians.

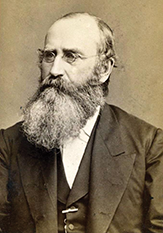

Charles Porterfield Krauth

A Lutheran Giant with Feet of Melanchthon

Among early Lutherans in America, few can be said to have had as profound an impact on the theological trends of his time as Charles Porterfield Krauth. In an era characterized by doctrinal apathy and rampant unionism, Krauth’s voice was one of the very few raised in defense of faithful, confessional Lutheran teaching. Among English speakers (Walther and the Missourians were German), Krauth was truly a Lutheran giant. Yet he was a giant with feet of clay. Like Philipp Melanchthon before him, his otherwise sterling theology exhibited scattered flaws, and, in the application of doctrine, he had a tendency toward toleration and compromise that somewhat vitiated his fine confession.

Krauth was born on March 17, 1823, in Martinsburg, Virginia. His father was a Lutheran pastor who later became a prominent professor at the Lutheran Seminary at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, where Krauth himself would eventually study. Krauth showed himself a theological prodigy from an early age, entering college when he was eleven and graduating from the seminary just after his eighteenth birthday.

In that era, little consideration was given to confessional unity, and most protestant denominations —including Lutherans—mixed freely. Krauth’s first call was to a congregation in Canton, Maryland. He found it to be of such mixed membership that one faction was even promoting universalism, the idea that all people will eventually be saved! He wrote despairingly to his father, “There is not to my knowledge one Lutheran in the congregation.” Here he got his first taste of how hard it is to be confessional and popular at the same time.

As the years passed, Krauth served in a variety of preaching and teaching positions in Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania. One thing that didn’t change was his determined Biblical scholarship and his voracious appetite for reading. He read everything. As he grew in scholarship and in familiarity with the Lutheran confessions, Krauth became a stronger and stronger advocate for pure Lutheran doctrine. By 1850 he had assembled a large theological library, and had himself translated many Lutheran confessional documents into English. At this time he describes himself as having “. . . come to the conviction that the whole truth of the authoritative Word was nowhere set forth with such clearness, purity, and fullness as in the collected Confessions of the Lutheran Church.” He became editor of an influential journal, Lutheran and Missionary. Later in life he helped found the then-conservative General Council, and served as its president from 1870-1880. Krauth’s magnum opus was a large book both historical and theological in nature entitled The Conservative Reformation and its Theology. No less an authority than C.F.W. Walther described Krauth as “. . . without doubt the most eminent man in the English Lutheran church of this country.”

It is notable that, at a time when the doctrine of church fellowship was poorly understood and seldom practiced, Krauth recognized that joint worship among those with differing confessions was contrary to God’s Word. He drew much criticism for supporting the famous Galesburg Rule: “Lutheran pulpits for Lutheran ministers only; Lutheran altars for Lutheran communicants only.” Yet, when it came to the actual application of this and other principles, Krauth’s gentle and irenic nature often tended toward accomodation rather than separation, even when separation was clearly called for.

Charles Porterfield Krauth, in his time, was a mighty influence for Lutheran confessionalism, and for faithfulness to the teachings of God’s Word. Indeed, his influence continues to be felt down to our day, in which you may well find The Conservative Reformation on your own pastor’s bookshelf. Yet it is a tragedy of American Lutheranism that his leadership, though it carried far, did not carry quite far enough. It is said that he led English-speaking Lutherans right up to the border of the promised land, but couldn’t lead them in. Following his early death at age sixty, none of his colleagues stepped forward to take up his confessional torch, and the General Council began a long theological decline. Whatever became of this church body, you ask? After many mergers and transformations, we know it today as the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, or ELCA.

Paul Naumann is pastor of Ascension Lutheran Church in Tacoma, Washington, and editor of the Lutheran Spokesman.